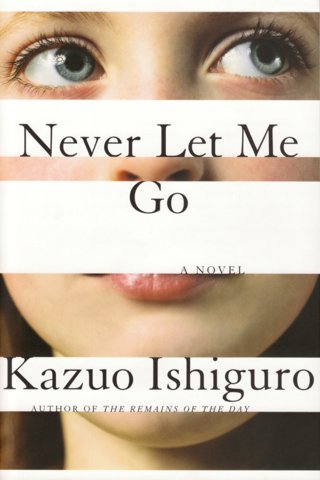

Never Let Me Go

Book Club

Aug 5, 2014

Tragedy, in the Shakespearian sense, comes from the inability of characters to rise above their flaws. The witches might tell the prophecy, but Macbeth hangs himself with it. Hamlet was never going to come gracefully to terms with his father’s death or seize power with conviction and force. The tragedy is that they were always going to damn themselves. The play just serves to show how.

Never Let Me Go is a tragedy of another sort. A more painful sort. But one that is no less inborn. It’s there in the background from the start. In spite of the movie, I managed to come to the book without knowing the premise. (The Library of Congress catalog data did tip the book’s hand, which is what I get for being the sort of person who reads copyright pages, I suppose.) But even without knowing what it was, the sense of it seeped through from the beginning. Like the students, I didn’t know what I knew, but I knew.

Thinking back now, I can see we were just at that age when we knew a few things about ourselves—about who we were, how we were different from our guardians, from the people outside—but hadn’t yet understood what any of it meant.

It’s the creeping sense of dread that makes the book. This won’t end well. This was never going to end well. And you’ll watch. But if there’s one flaw that leads to the doom of the characters in Never Let Me Go, it’s that they accept their mortality. Like we accept ours. Like us, the greatest ambition of the clones is to put it off for a few years. Maybe if they love enough, they can get three more years. Toward the end, I thought about how I wouldn’t give them the satisfaction. I’d kill myself. Or kill them. Why go peacefully to have my organs harvested? Why should they deserve to extend their lives when reaching thirty-five is so much to ask? But they don’t. It doesn’t even seem to occur to them.

And I suppose it doesn’t really occur to me, either. I’ll die, someday. And probably without the satisfaction of relieving someone’s suffering by the way. And unlike the normal humans who drift in the background of Never Let Me Go, I’m not about to go violently to my end, taking someone else out in the hope that I might buy myself a few more years. Maybe that’s tragic. Or maybe it would only be tragic to an outsider, someone who hasn’t known since birth that they were going to die sometime before the end of their first hundred years.

It doesn’t really matter how well your guardians try to prepare you: all the talks, videos, discussions, warnings, none of that can really bring it home. Not when you’re eight years old and you’re all together in a place like Hailsham; when you’ve got guardians like the ones we had; when the gardeners and the delivery men joke and laugh with you and call you “sweetheart.”

But if it were really that simple, it wouldn’t be so human. I do mourn my own death. And the clones of Never Let Me Go may not fight their creators, but they know. They know they were made to suffer and die. And though they may abet their creators in little ways, they know their deaths are a plan that someone made. Maybe it would be something like believing in god but not the afterlife.

The creeping knowledge of what it is comes on slowly and makes me wonder when, exactly, it was that I became aware of the inevitability of my own death. I don’t recall ever not knowing. There was no big childhood moment of loss. One grandparent of each sex from each side died before my own birth, and the remaining two survived to see me reach adulthood. I do remember a moment of dread as a child when I became aware of environmentalism and the implicit threat that the world might not outlive me. I suspect that, like much else, I became aware of the concept of death through osmosis, overhearing conversations between my parents that I was not quite old enough to appreciate, so that death was never a concept absorbed full-force. There was no single moment of transition from ignorance to realization. I processed it, instead, in steps, ranging from blind acknowledgement to the ever more concrete understanding that my body will one day fail.

Maybe from as early as when you’re five or six, there’s been a whisper going at the back of your head, saying: “One day, maybe not so long from now, you’ll get to know how it feels.” So you’re waiting, even if you don’t quite know it, waiting for the moment when you realise that you really are different to them; that there are people out there, like Madame, who don’t hate you or wish you any harm, but who nevertheless shudder at the very thought of you—of how you were brought into this world and why—and who dread the idea of your hand brushing against theirs.

I wonder, though, if it is even more innate than that would suggest. Perhaps there really is something about being mortal that sows seeds of that realization without need of any explanation. Maybe we learn through observation as infants that people are not infinitely varied in age. Maybe we are smart enough, even then, to observe that few, if any, exist beyond our grandparent’s generation. And we begin to figure it out from there. Or maybe there is something wired into our brains through eons of evolution that sets up the concept. After all, as impossible as death may be to contemplate, infinity is the harder to grasp by far.

If, like me, you go into Never Let Me Go without preconception (excepting my unfortunate encounter with the label “Cloning—Fiction” on the copyright page), your understanding of what it is evolves along with the students. You start with the somewhat ominous words “carer” and “donor” dropped on page one along with the implication that a career ending at thirty-one is, if anything, on the long side. In what follows, death paints an inevitable backdrop, but for a time, it is only distantly relevant. The children have their lives. Their concerns, for the most part, have nothing to do with their fate, and as a reader you forget to be concerned with it. The failure to mention parents does stick out, and along with the lack of any concept of holidays, it obviates any need for confirmation via copyright page spoilers that cloning is involved. But while the combination of “Cloning—Fiction” with “carer” and “donor” is enough to void any doubt, the why is left unsaid. And for a while, you, the reader, get to pretend along with the students that there might be some more innocent source to that pattern. But you know better. And they know better. And you know they know. And so you become implicated along with the guardians at Hailsham, sympathetic, but ultimately, like Miss Lucy, burdened by the knowledge that these happy children whose lives you are enjoying exist only to be slaughtered. And that tension—whether and how much do they understand how unfair that is—coats everything.

The first time you glimpse yourself through the eyes of a person like that, it’s a cold moment. It’s like walking past a mirror you’ve walked past every day of your life, and suddenly it shows you something else, something troubling and strange.

If I have one qualm, it is in the way the book allows itself a moment of uncharacteristic release. Kazuo Ishiguro is unable to resist a climax, allowing a voice for the guardians to lay it all out and explain, in stark terms, how there is no hope, not even for three more years. Not even for those in love. We get to have that moment of satisfaction, the chance to explain why. Why Hailsham, why nothing will change, why make an effort to raise students instead of simply breeding clones. As little satisfaction as the answers hold, they break the tension. They let us sympathize with Tommy when he gives a last tantrum. And they give us more than we ever get by way of answers about our own mortality.

I can’t help but think that the book would have been more powerful without that last bit of resolution. If they never knew, for sure, the why of it all. If they decided it would be too painful to learn they couldn’t get a deferral. If they went calmly to their fate, not because they knew all other paths were closed, but because it was the one path they knew. Because following that one path, even through pain and death, was less frightening than contemplating the possibility that their hope was futile or, worse, that all they had to do to be spared was ask.