Kentucky Route Zero

Game Club

Apr 17, 2015

It’s somewhere after 4 AM, and I’m fighting my mouse cursor, trying to keep it from the button that will make me take a drink. It seems avoidable, the obvious right choice, but as I click to move on, the cursor slips, moving deliberately back to the drink. There’s a slowness to the movement, but it happens quickly enough that I’m not immediately sure what happened. Did the game register my click and contradict me? Or did it anticipate me somehow? Did it place me in one of those dreams where you see in real time, but your every movement is through molasses? Has it extended that instant while my finger depresses, drawing the cursor back while I watch, unable to stop what is already in motion? When the moment breaks, and my finger completes it’s eighth inch of travel, I’m hovering over the drink. I take it.

My hazy confusion is informed by the hour and also by the fact that my own left hand is clutching a now empty glass of Rowan’s Creek Bourbon. “I don’t have a drinking problem” is the sort of thing people say when they have one, so I won’t. Unlike the protagonist I am failing to control, however, alcohol has not ruined any portion of my life. Still, it seems significant that I like to play Cardboard Computer’s Kentucky Route Zero like this: alone, way past my bedtime, and a little drunk on bourbon.

I finished Act III, the middle and thus far most ambitious act of this so-called magical realist adventure game some months after its release. That it took me so long is largely due to this habit. But while it might be insensitive to drink Kentucky straight bourbon while playing a game centered on the end of a life ruined by it, I stand by my method. Kentucky Route Zero is a smoky sort of game, viewed best from a haze at the end of the night when you’ve just barely enough energy left to go on. It invites you to be distracted. To sit and contemplate the scene before you, even though it has little to do with the path ahead. Or so you think. Because it also invites you to begin believing that it’s all connected, that each random bit of someone else’s story is a fragment of your own.

Games have been struggling to come into their own as a narrative platform for many years. Their inherent interactivity makes them well suited to producing a sense of immersion, but it’s also a trap. Few stories stand up to the prodding of player choice, and it is nearly impossible to pace a story that must wait on the player to progress. So for years, most games that tired to tell a story did so by dividing into two, the game you play, and the movie you watch, via cutscenes.1 Add to that the relative expense of making a game and the hit-driven business model of most publishers, and you’re lucky to ever transcend a summer action blockbuster.

Recently, however, digital distribution, together with greater accessibility of game-making tools has lead to a flowering of smaller projects created by one to a small handful of people. These don’t need to attract the millions of players most traditional publishers require to justify making a game and so are free to explore more niche subjects. They can make choices likely to be adored by some, hated by others, and met with general indifference by most. Many of these games stake out territory closer to installation or performance art than most people’s concept of a game.2 Freed from those constraints, some games are making strides in advancing narrative forms, trying to find new ways of telling stories that are enhanced by, or wouldn’t even be possible outside of, the context of a game.

When you start up Act I, Kentucky Route Zero looks, and to some extent behaves, like a ’90s era point and click adventure game. For those who didn’t spend hours Questing with Kings or Monkeying with Islands, a point and click adventure game presents you with an avatar you can move around within a diorama by clicking on the ground. Adventure games have always been well-suited to narrative. They evolved, after all, from text adventures which share some DNA with choose-your-own adventure books and whose modern branch is often referred to as interactive fiction. And even when point and click adventure games were still a staple of the main stream, they were host to some of the first and, to this day, most successful attempts at humor in games.

The greatest strength of adventure games has always been in creating a sense of a living world. Perhaps because they avoid the uncanny valley, adventure games have a much easier time at this than first person 3D games that allow you to walk through an invented world as if seeing it with your own eyes. Instead, you discover the world by poking and prodding it, seeing how it reacts and where it takes you. The typical adventure game player clicks on everything, tries to open every door and combine every item, just to see how the world will respond, learning about the world like an infant who keeps dropping different objects to see how their parents will react. Classic adventure games had obscure puzzles that encouraged this behavior, but exploration has always been the primary drive for me, with puzzles being less the core of the game than an obstacle to prevent you from rushing past it.

And yet successful and laudable as these games were, until Kentuky Route Zero, I never played a game that I thought of as a form of literature.3 And, let me be clear, games don’t have to be literature to be worthwhile. Games are games and literature is literature, neither is more or less worthwhile for how closely it approaches the other. But what Kentucky Route Zero manages here is to approach storytelling through a set of constraints completely different from those imposed by the form of the traditional novel.

When you start up Kentucky Route Zero for the first time, it isn’t entirely clear what you’re looking at. Not knowing yet what sort of beast this game is, it is easy to see the first act as an extremely simple adventure game. In fact early reactions were tepid, with some complaining that it seemed deliberately obtuse and rather thin. There are no puzzles. Possibly the only choice with lasting impact that you make is to name your dog. On a future play-through, though, you can see the foreshadowing from the very start.

Very nearly the first words the game presents you with are these: “JOSEPH: Damn! Did you hear that wreck? Truck full of bottles — I dunno, beer bottles? Whiskey? Lost a tire or something, and spilled booze and glass all over the interstate!” To say it’s implied that it was you in that wreck would be too direct. That’s not the sort of story being told, where a single twist brings it all together. But the theme sure keeps coming back up. It isn’t so much that you were really in that accident as that the sound of shattered bottles of booze haunts Conway, the main character of the game.

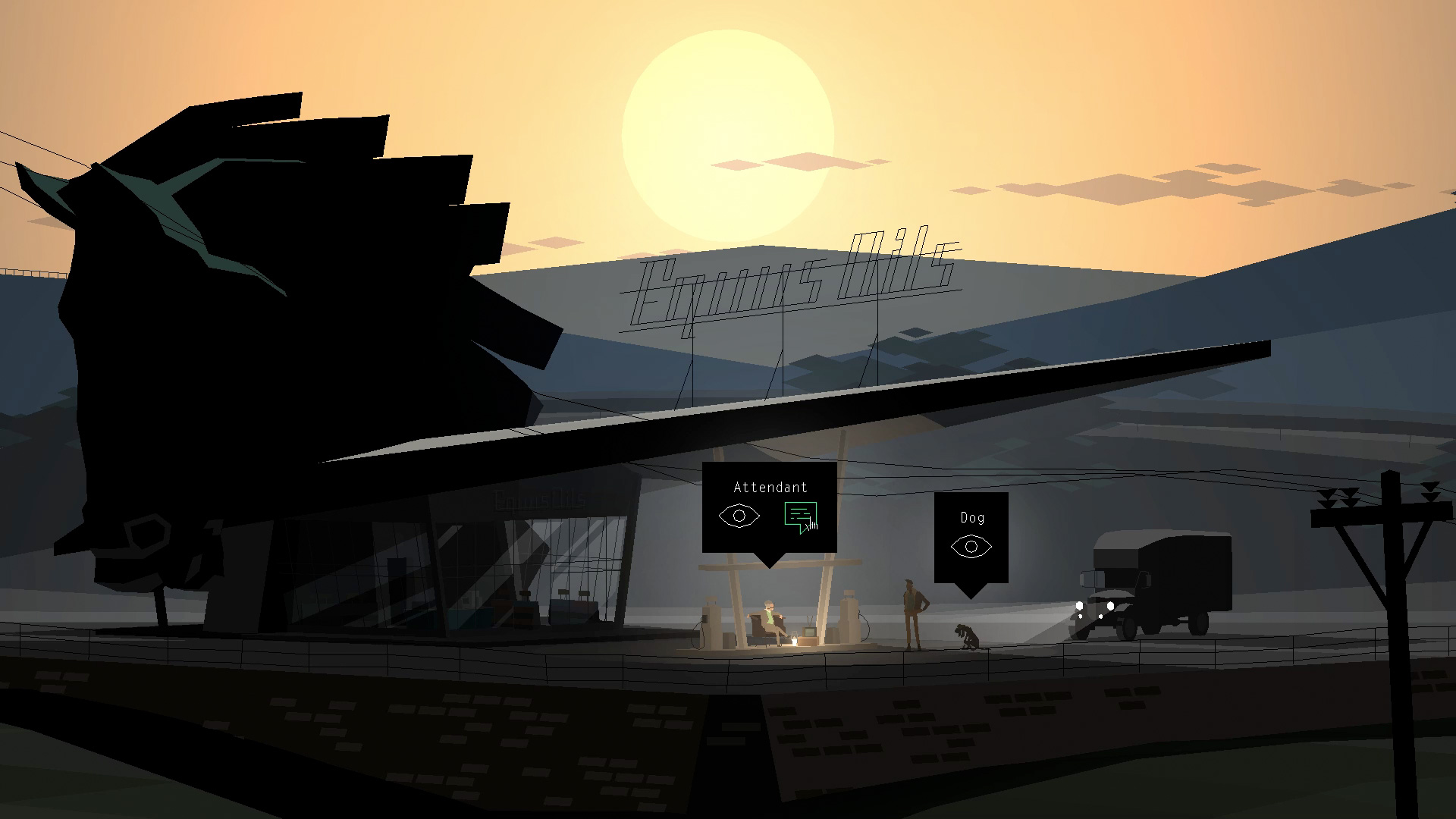

The aesthetics of the game are spare, with flat-shaded, notably non-antialiased polygons forming the world. But that spareness makes the little touches stand out. The text is uniformly presented in the form of a play with descriptions reading as stage directions: “JOSEPH sits between gas pumps in a Queen Anne armchair. His hair is gray and his glasses darkened.” This is reinforced by the flash of title cards that introduce each scene: “ACT I, SCENE I. EQUUS OILS.” And yet for all the hints of a proscribed order to things, the scenes aren’t so regimented. If you leave Equus Oils and return again later, you may get a new scene or, if you never do return, you may not, with future scenes simply taking one number lower. So you are acting out a play, but not a fixed one. Rather, it is a play that forms itself around you as you walk through it.

Much of the choice you have presents itself this way. Dialog options aren’t opportunities for story branching or a matter of choosing different approaches, like deciding to be friendly or angry. They don’t change the story, or even seek to create that illusion. Instead they offer a choice between areas of backstory to fill in. They let you chose what other thing this present moment calls to mind or which character is the one to speak up. In a few memorable cases, they ask you to participate in the creation of a poem from constituent blocks. This conspires to craft the impression that you are drifting, unable quite bring to mind the details of your waking life, but as the events unfold before you, a piece or two comes to mind, and you can’t help but spend a little time following the thread.

Likewise text in the game isn’t simply the presentation of static words, but something more alive. Words relayed from a computer screen flicker with scan lines, and when The Zero is mentioned it pulses and shimmers as though the word itself, even when presented in this world, isn’t quite a part of it. It’s little touches like these that begin filling in the story before any of it is addressed directly. An early heart stop-inducing moment comes when Conway tries to log onto Joseph’s computer. If he gives his own name instead of Joseph, the computer replies with the simple and existentially terrifying, “User Conway is not real.” This, it turns out, is the way the computer has of telling you it doesn’t have a record of something. When you request to play a game, it also responds (perhaps somewhat cheekily), “‘Games’ is not real.”4 This phrasing is significant, if not directly revelatory. After all, from the computer’s point of view, if something isn’t in its data banks, it isn’t in the world. And to say something isn’t in the world is another way of saying that it ins’t real.

Like works of magical realism in other forms, much of the power in Kentucky Route Zero comes from these sorts of unremarked coincidences or conventions that seem just a few degrees off. At times more than a few, when the game veers off into outright absurdism. At one point in Act II, you are faced with a multi-story office building that is normal enough given the strangeness that surrounds it. Yet one floor is labeled, simply, “Bears.” And sure enough when you ride the elevator past, you see them, lumbering in an indoor forest, bears. It isn’t so much the bears themselves that are noteworthy as that no one other than the player, not even the main characters themselves, feels this warrants any sort of comment.

Given the dependance on an accumulation of vignettes to paint the larger picture of the story, it isn’t a surprise that the game took a couple of acts to really show its depth. What is, perhaps, somewhat of a surprise is that it has so far avoided being weighed down by them. It would be all too easy for a game like this to become a scattered collection of random events whose novelty wears off when you see one too many and begin to feel that they are strange only for strangeness sake. On the flip side, in their desire to tie everything together and make a point, it would be easy to go too far into moralizing. The events of Act III come closest to this with their direct exploration of alcohol’s grip on the characters, but (and beyond the anecdote I presented at the start, I won’t spoil it) it has managed, so far, to walk that tightrope and remain, simply, poignant.

There are so many open threads left for them to explore, that I’m not sure where to guess Cardboard Computer will take the story in the final two acts. Things presented as early as the first scene (Xanadu gets mentioned in an email on Joseph’s computer long before it becomes a central, if baffling, part of Act III) have come into steadily sharper focus over the course of the acts. They might chose to continue filling in those details, making it clearer how Xanadu and Joseph and The Zero relate to the more mundane characters of the world. But I sort of hope we never really find the answers and instead get bored and wander off in some new direction. Because no concrete answer could match the vague beauty of the questions posed in these first three acts. Whatever path they choose, I can’t wait to continue to wander along that aimless loop of The Zero that never seems to take me where I’m going, but never fails to bring me somewhere that reflects where I’ve been.

-

This sounds derisive, and I suppose it is, but I’d argue it can still be a worthwhile technique. Something about controlling the actions of a character can deepen my investment in an already well-told story. So even if those sorts of games are essentially a game kludged together with an animated movie, if both are well made they can be more than the sum of their parts. The story they tell, however, is never likely to ascend past the faint praise of “good… for a game.” ↩

-

Indeed the question, “is this a game?” has plagued many of these smaller works, especially when they try to get access to coverage or publishing platforms. Like any argument over semantics this gets rapidly tiresome and tends to reveal more about the arguers than any fundamental of the subject. Personally I tend to err on the side of calling them games because they have evolved from more traditional games and there’s no other good word for them. It’s rather like arguing whether a live news broadcast, an awards show, a sitcom, and a miniseries are all television shows. No one is trying to deny there are great differences between them, but there’s little sense in getting bent out of shape over lumping them together if only for the arbitrary reason that they were historically developed to be displayed via the same technology. ↩

-

There are, of course, hundreds, thousands, of games I haven’t played, so I am only speaking about personal experience, here. ↩

-

See above, “Is it a game?” ↩