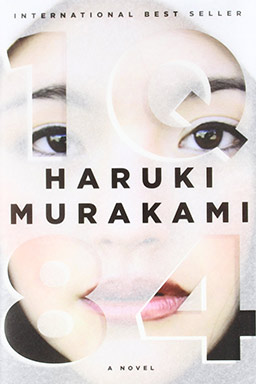

1Q84

Book Club

Mar 11, 2014

When thinking back over Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84, I like to start with the end (and that will, of course, make spoiler warnings go double here). Where are we left at the end of the book? We have our protagonists, Tengo and Aomame, together, expecting a child, holding hands and viewing the single moon over the Tokyo skyline. The remainder of the book that leads up to that point can be seen as their attempt to answer (with apologies to The Talking Heads) the question they may ask themselves, how did they get there?

The story they tell might not agree with the one an observer from their left-facing Esso tiger, single moon world would give, but it is how they experienced it. Does that make their story an allegory? Or some form of fabrication? Perhaps that’s a foolish question when it comes to fiction. It’s not unlike asking whether Dorothy’s trip to Oz really happened. Of course it didn’t, and then of course it did. It’s a fiction, and so a sort of lie, but then again a story, and so a sort of truth, and it’s status as both isn’t really affected by an author’s statement about the reality experienced by Dorothy in bed or Tengo in a hotel room in Tokyo. Dorothy on the Yellow Brick Road had her adventures regardless of whether that Dorothy exists as a past version of the Dorothy in the “real” world. (Which world, of course, is just as fictional as Oz for all of being named Kansas.) Of course it’s a great deal more subtle in 1Q84, where the fantastical elements of that world are few, and where even those are not widely seen. This only serves to emphasize the foolishness of the distinction. After all, our memory of the past is always a fiction.1

“And also,” the driver said, facing the mirror, “please remember: things are not what they seem.”

Things are not what they seem, Aomame repeated mentally. “What do you mean by that?” she asked with knitted brows.

The driver chose his words carefully: “It’s just that you’re about to do something out of the ordinary. Am I right? … And after you do something like that, the everyday look of things might seem to change a little. Things may look different to you than they did before. … But don’t let appearances fool you. There’s always only one reality.”

The place Tengo finds himself at the end of the book isn’t so strange. Or, rather, it is very strange, but also commonplace. Tengo, like so many of Murakami’s protagonists is just over edge of thirty. Like many at that age, at the start of the book his life has settled into a period of perpetual transition. Not a lot changes, but there is little solidly established about it. He rents a small apartment with few worldly possessions. While he displays great talents as both a mathematics teacher and an author, he’s made little mark in either field. No doubt some students remember him fondly, but he isn’t even a full time professor, only teaching courses to help students cram for their entrance exams. In the context of 1980s Japan, with a culture of lifetime employment, this temporary status is all the more profound.2 Likewise he seems to lack commitment to his writing. He considers it his primary ambition, but he seems content to take it slow, wandering about trying to find his style, doing petty tasks for his mentor, Komatsu, an editor at a literary magazine.

His social life isn’t much more grounded. He has a few friends, it seems, but they don’t play any active role in his life or the novel. His family consists of his father from whom he is estranged. Even his romantic life seems designed to avoid commitment while simultaneously preventing change. He sees an older, married girlfriend exactly once a week. He seems genuinely fond of her, and she expresses a possessiveness toward him, but he can’t even contact her directly. The relationship is tailor made to satisfy his minimum needs for intimacy without any danger of developing further.

By the end of the novel, Tengo has, essentially, a family. You could imagine a much more mundane path from here to there than occurs in the book. Tengo, lonely, even if he doesn’t quite realize it himself, meets a woman he shared a moment of innocent intimacy with when they were children. They rekindle their feelings for each other almost immediately, and before he knows it, she is pregnant and they are starting a life together. Like I say, a familiar story, but one that surely feels world-changing when it happens to you.

It is worth, also, considering the significance of that moment when they held hands as children, and the way they each fixate on it. How much was their fixation with each other something that preexisted their romance, and how much is it a part of the narrative that they weave after the fact? A piece of magic when viewed as the foundation of their new lives and the life of their child, a fleeting memory, otherwise. After all, the mutual fixation seems to appear out of nowhere mid-story. Though they both take it for granted and carry it forward into the new world where they are a couple, it has the contrived feeling of an element from the 1Q84 world, not the original, right-facing Esso tiger world. Perhaps the extra significance both Tengo and Aomame place on that moment is a part of the fictional world Tengo has created.

How do you explain such a profound change in your life? When you can’t imagine what your life would be if you hadn’t met someone? When it seems like some great force in the universe must have arranged the chances just so, in order to make your life possible? (When, of course, any other life you might have had would also have been a sequence of seemingly fated events, because they are the events that happened.)

Most of us do it by telling a story, even if we don’t realize what we are doing. It’s not usually so fanciful. Even if we use the word “fate,” we rarely put a face to it. But we do invent a story, picking out the events we see as significant after the fact, simplifying them, putting them in order, and speaking of how we looked across the room and knew, or, even if we didn’t, we will at least speak of that party, that glance, that holding of hands, that kiss. And while we might not have the imagination to invoke a conspiracy of little people or to explain the suddenness of going from a loner to expecting a child with a virgin birth,3 sometimes that is how it feels.

As an aside, I was convinced for a while early on that the Aomame portions were written by Tengo. That they were, perhaps, actual excerpts from his draft. So Tengo, reminded of Aomame when he sees the mother and daughter Society of Witness members on the train, comes to wonder what happened to her over the years and invents a life for her. He makes her the protagonist of his story set in the world of Air Chrysalis and falls for her, imagining that she might be out there remembering him. Of course this doesn’t fit with his assumptions about her later on when he starts actively seeking her, but it’s an interesting idea within the context of her being pulled into the 1Q84 world.

When morning comes you will be leaving here, Tengo. Before the exit is blocked. …

This was the cat town. There was something specific that could only be found here. That’s why he had taken the train all the way to this far-off place. But everything he found here held an inherent risk. If he believed Kumi’s hints, these risks could be fatal. By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes.

It was time to go back to Tokyo—before the exit was blocked, while the train still stopped at this station.

So I appreciate the way in which 1Q84 paints the way the great changes of life can feel. How unreal, and overwrought, and also deeply, crushingly, mundane it can all be at once.4 Unfortunately the way it gets there isn’t without its flaws. For the record, since this is the first article of this type I am writing, I don’t see the need to write literal book reviews in the sense of appraisal of quality (and I’ll never hand out a score). Either there is something worth writing about or not. But I can’t see writing about 1Q84 without discussing what a frustrating book it was to read. When it’s good, it’s really good, but there were times when the force driving me to keep turning the pages was a desire not to get to the next bit, but to be done with the current section more quickly.

It’s not that the book is too long, though it is a long book, or even that it starts slow, though it does. I rather felt that the deliberate pace of most of the book contributed to the mood, and while I found the setup of the whole “literary conspiracy” to have Tengo ghost-rewrite Air Chrysalis a bit strained,5 the initial introductions of Tengo, Aomame, and Eriko were all intriguing enough to make me want to read more. And while there are a number of digressions throughout the book, such as the discussion of the Gilyaks, even those aren’t the problem and when they work, they add depth and texture to the world.

Where it falls down is in repetition. The whole book felt badly in need, ironically, of an editor’s rewrite. It isn’t enough to mention the stakes should their fraud in rewriting Eriko’s novel come to light. They have to do it again and again, taking what is a somewhat contrived situation as it is and throwing it, repeatedly, to the foreground where it’s flaws stand out. We are reminded repeatedly that this might be dangerous to the point that when the cracks do begin to show it produces anticlimax more than a building of dread. Whole sections of (admittedly important) character background are introduced only to be largely repeated not half the book away, but in the very next section. For an author who seems to generally trust his readers to either pick up on things or not, this book seemed uncharacteristically blunt in places. Tengo’s childhood Sundays going door to door with his father and their similarity to Aomame’s are repeated to the point where one feels little need to ask whether it will be on the exam.

And that’s all unfortunate, because the world that Murakami builds is a compelling one, and if he had trusted readers to pick up on those important bits of Tengo’s history without the many retellings, he might have had more time to explore any number of bits of beautiful strangeness that he only hints at. In the end, we’re left with a flawed but worthwhile read. No, the threads don’t all tie together at the end, and you are left with little understanding of the mechanisms by which the 1Q84 world operate, but those elements aren’t the main point of the book. The point, in my mind anyway, is to induce that eery feeling of not knowing your place in the world and to explore how your view of the world changes as you decide what that place should be. And on that score, 1Q84 succeeds.

-

As it happens the next book I read after 1Q84 was Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending which deals with this subject directly. You couldn’t find two more different books in many ways, but both deal, at their core, with the way we turn our lives to fiction. Update: I discuss The Sense of an Ending here. ↩

-

This alienation from typical Japanese style employment is one of the common traits Murakami’s protagonists often share. ↩

-

A virgin birth which nonetheless conveniently leaves no doubt as to the parentage in either parent’s mind. ↩

-

I’m reminded of Buffy the Vampire Slayer which takes the angst of high school (and later young adulthood) and personifies it in the form of actual demons. ↩

-

Perhaps there is something lost in translation here, but it seemed to me that the scandal Komatsu and Tengo invited by the arrangement was there practically by design. Would it really have been such a big deal to have a co-authored book? Or to openly list Tengo as a mentor who helped Eriko revise it, lying only about the extent of his involvement, something no one could really prove? It seems like the only way it could turn out to be a scandal would be to do as they did and insist that they had nothing to do with it. ↩